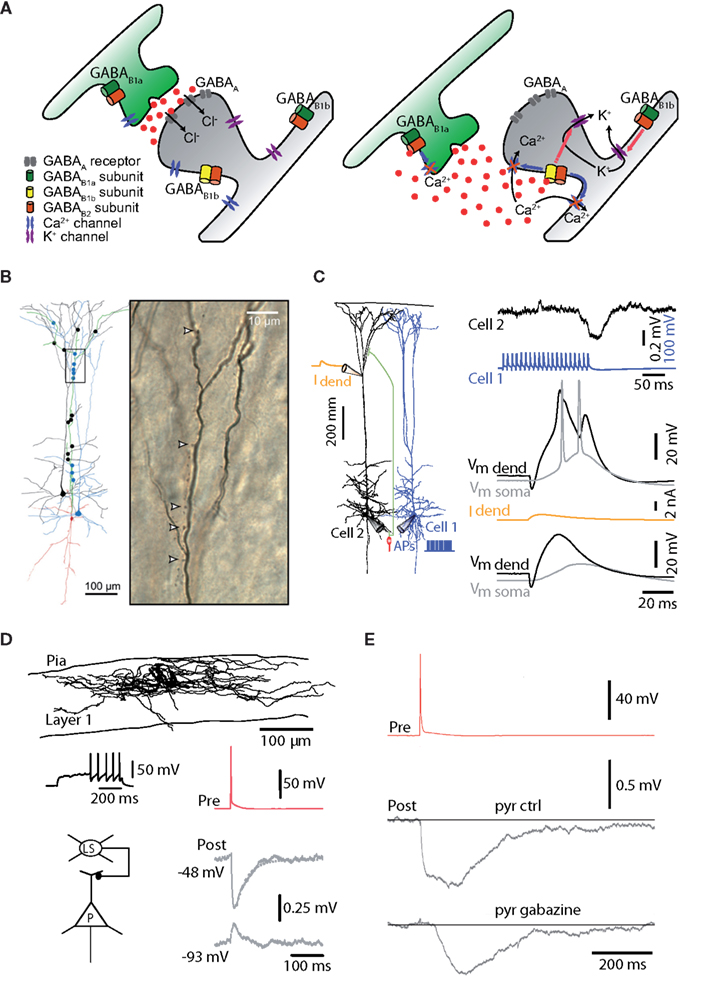

Neuroscientists have hypothesized that these dendrites can act as compartments that perform their own computations on incoming information before sending the results to the body of the neuron, which integrates all these signals to generate an output.

Mathieu Lafourcade, a former MIT postdoc, is the lead author of the paper, which appears today in Neuron.Īny given neuron can have dozens of dendrites, which receive synaptic input from other neurons. “Our hypothesis is that these neurons have the ability to pick out specific features and landmarks in the visual environment, and combine them with information about running speed, where I’m going, and when I’m going to start, to move toward a goal position,” says Mark Harnett, an associate professor of brain and cognitive sciences, a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research, and the senior author of the study. In the neurons that the researchers examined in this study, it appears that this dendritic processing helps cells to take in visual information and combine it with motor feedback, in a circuit that is involved in navigation and planning movement. These differences may help neurons to integrate a variety of inputs and generate an appropriate response, the researchers say.

The researchers found that within a single neuron, different types of dendrites receive input from distinct parts of the brain, and process it in different ways. Researchers at MIT have now demonstrated how dendrites - branch-like extensions that protrude from neurons - help to perform those computations. Within the human brain, neurons perform complex calculations on information they receive.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)